History

Discover the story of Dumfries House from the 18th century to today, and its transformation from stately home into an extensive cultural and education estate managed for the benefit of the local community.

1750s

Dumfries House is built

Dumfries House was designed by the Adam brothers and built in the 1750s as a residence for the 5th Earl of Dumfries. Originally named Leiffnorris House, the Earl decided to name it Dumfries House, in line with his title, once construction had begun.

1760s

Decorating the interior

The Earl furnished the House according to the rococo interior design style. He hand-picked the finest furniture from the workshop of Thomas Chippendale.

1847

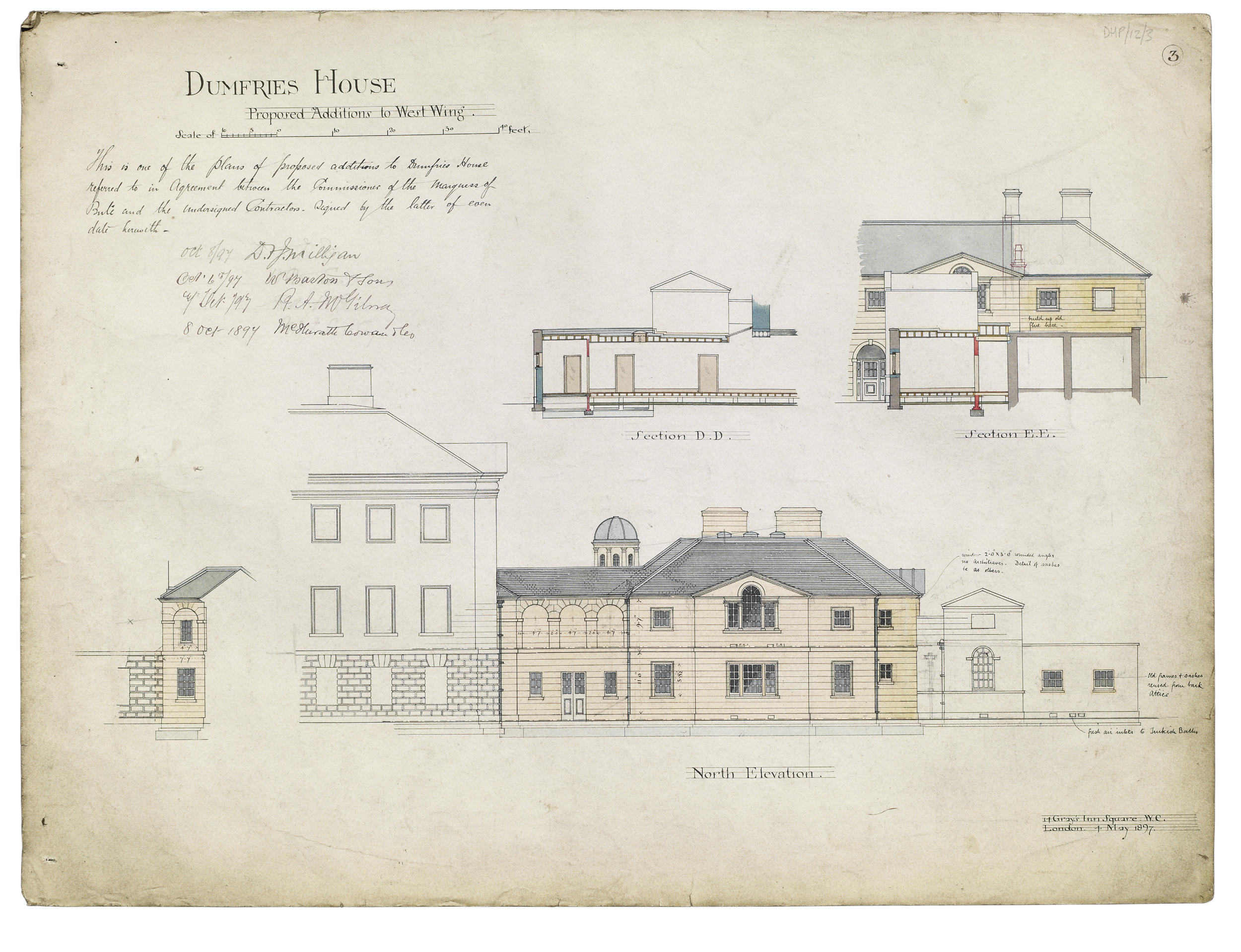

Extensions to the House

John Patrick Crichton-Stuart (1847-1900), 3rd Marquess of Bute, inherited the estate at the age of six months. He went on to add extensions to the east and west wings of the house, designed by Scottish architect Robert Weir Shultz.

1993

The House remained a family home until its last remaining occupant, Lady Eileen Dowager Marchioness of Bute, passed away. The House remained in the family, who oversaw its maintenance, but it was no longer used as a primary residence.

2007

Saving the House

When Dumfries House, its grounds and contents were put up for sale, its future looked uncertain. Two auction dates were set in July 2007, however a consortium led by the then Prince of Wales succeeded in purchasing the house and contents – saving Dumfries House for the nation.

2010-2011

Interior restorationThanks to charitable donations, The King’s Foundation carried out an ambitious programme of refurbishment and conservation at Dumfries House, restoring the original beauty of the interiors and many pieces of furniture and art.

2012

Repurposing the estate’s buildings

The estate’s buildings were repurposed in innovative ways. The 18th-century coach house and adjacent stable became our Coach House Café. The sawmill was renovated to full working order and became the Craft Workshops, equipped with classroom, wood workshop and stonemason’s shed.

2012

Dumfries House Lodge

The Dumfries House Lodge opens its doors to visitors looking for luxury bed and breakfast accommodation, renovated from a derelict farm building on the estate.

April 2013

Supporting careers in hospitality

The state-of-the-art Belling Hospitality Training Centre opens, where we deliver programmes training young people in hospitality skills to enter the industry. The Woodlands Restaurant opens soon after.

September 2013

A beautiful arboretum

The King’s vision for a new arboretum was realised with a leafy ten-acre garden on the estate. At the centre of the plot lies a woodland shelter, designed and built by students from The King’s Foundation Summer School.

2013

Many of the most important pieces in the House have now been restored, including the collection of 18th-century Scottish furnishings. All four tapestries in the Tapestry Room have been revived.

2014

Repairs to Adam Bridge – a 1760 John Adam design and one of the most important estate bridges in the UK – are completed. Signs of vandalism and damage were removed, stonework was replaced and the road was resurfaced.

With two classrooms, a potting shed and a meeting room, the Pierburg Education Centre launches to deliver our programmes in horticulture and farm-to-fork education for young people.

July 2014

A new Walled Garden

The Queen Elizabeth Walled Garden – one of Dumfries House’s most ambitious projects – opens to the public. Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II opens the garden to the public, and within just four weeks, we welcome almost 3,000 visitors.

2015

The 52-bed Tamar Manoukian Outdoor Centre and Amersi Foundation Activity Area opens, offering residential courses for youth organisations from the local area and around the world.

2016

The front-of-house garden is redesigned by Michael Innes, introducing a central fountain, ornate box hedges and two yew mazes.

April 2015

STEM learning begins

Our Morphy Richards Engineering Education facility opens. The facility is the largest of its kind in Europe and provides school programmes in STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) for school pupils.

2015

Education farm launches

Our Valentin’s Education Farm opens. Working with the Rare Breeds Trust, the farm teaches preservation and sustainability in farming through our selection of rare livestock.

April 2016

Temple Gate restoration complete

Restoration of the Category A-listed Temple Gate is completed. The gate had been in a significant state of disrepair when work began.

2016

Expanding into the community

The regeneration of Dumfries House steps further into the local community. The refurbishment of New Cumnock Town Hall is completed in October and reopened by the then Prince of Wales.

July 2017

A new development

Restoration is completed of New Cumnock Swimming Pool – Scotland’s only public, outdoor, heated freshwater swimming pool.

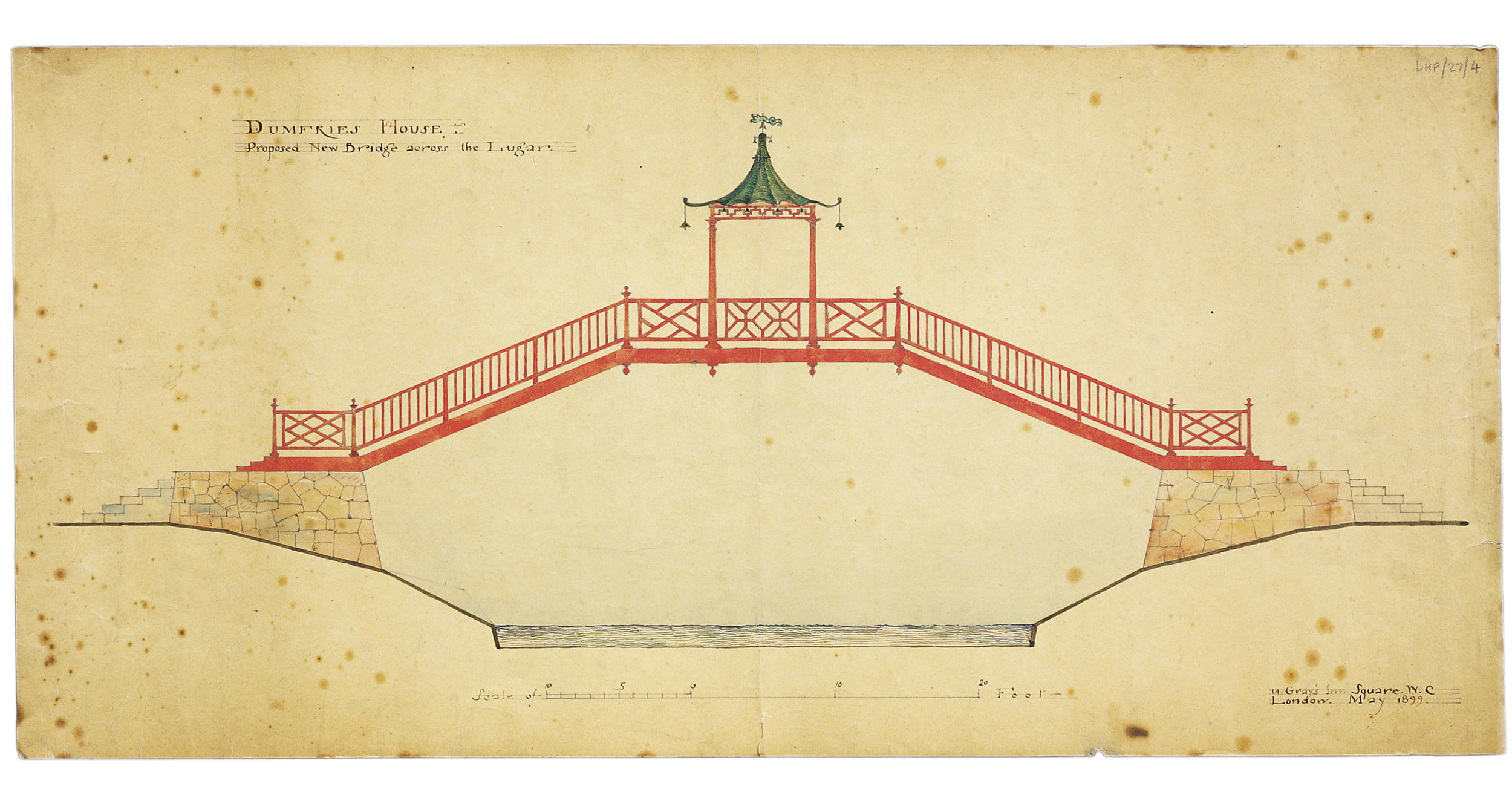

2017

A new river crossing

The Chinese Bridge opens to the public. Based on an 1899 drawing by architect Robert Weir Schultz, architect Keith Ross worked with the then Prince of Wales to bring the design to life.

2019

Supporting health and wellbeing

Our Health and Wellbeing Centre is opened by the then Prince of Wales, designed to deliver a range of holistic services to support local people.

2023

King Charles III accedes to the throne, and The Prince’s Foundation becomes The King’s Foundation, signalling The King’s ongoing commitment to our charitable work.

September 2023

A new farming education centre

His Majesty The King officially opens The MacRobert Farming and Rural Skills Centre. The Centre, first opened in 2022, focuses on providing training and upskilling opportunities in the farming and rural skills sector.

January 2025

Celebrating 35 years

His Majesty launches The King’s Foundation’s 35th anniversary celebrations with a time capsule capturing the work of the Foundation, to be buried on the Dumfries House estate and opened in 100 years’ time.