News. Robert Adam, one of Scotland’s foremost architects

11th of January, 2018

The 5th Earl and the architect who dreamt up his grand home had more in common than a shared gusto for extravagant interior design; evidence suggests they were on very cordial terms.

“Robert Adam stayed with the Earl while the foundations were being dealt with,” says Head Guide Alex MacDonald. He wrote to his mother from Dumfries House in 1754, shortly after the foundation stone was laid, and said he found the Earl and his family in ‘good health and top humour’. So he’s practically a guest, as opposed to being a tradesman or contractor.”

The friendship would have delighted the young architect, according to MacDonald, as it would have considerably enhanced his social standing. “He was very ambitious,” says MacDonald. “He would certainly have sought out the company of aristocrats. In fact, when he went on his European tour, he asked his brothers, when they wrote to him in Italy, to address the letter to ‘Robert Adam Esq’, rather than ‘Mr Adam, Architect’. He felt that on his travels, to be seen as an architect or an artist was to be seen as a tradesman and not a gentleman.”

Adam would certainly go on to garner the success and social standing he so craved. His portfolio of buildings, at the time of his death in 1792 aged 64, included west London’s Syon House, Bath’s Pulteney Bridge and a host more grand country houses, whose lavish interiors can be attributed to Adam’s fervid imagination, along with their edifices. Combined, these works have made his surname synonymous with a golden age of architecture.

With vast success, of course, comes friendships in high places. One of the first residents in the monumentally ambitious Adelphi building, designed by Adam and his brothers and built by The Thames between 1768 and 1772 – a vast, opulent edifice, calling to mind a Roman emperor’s palace – was the actor, producer and playwright David Garrick. Through the influence of John Stuart, the 3rd Earl of Bute and a friend of King George III, he was appointed architect of the King’s Works in November 1761 and served as MP for Kinross-shire.

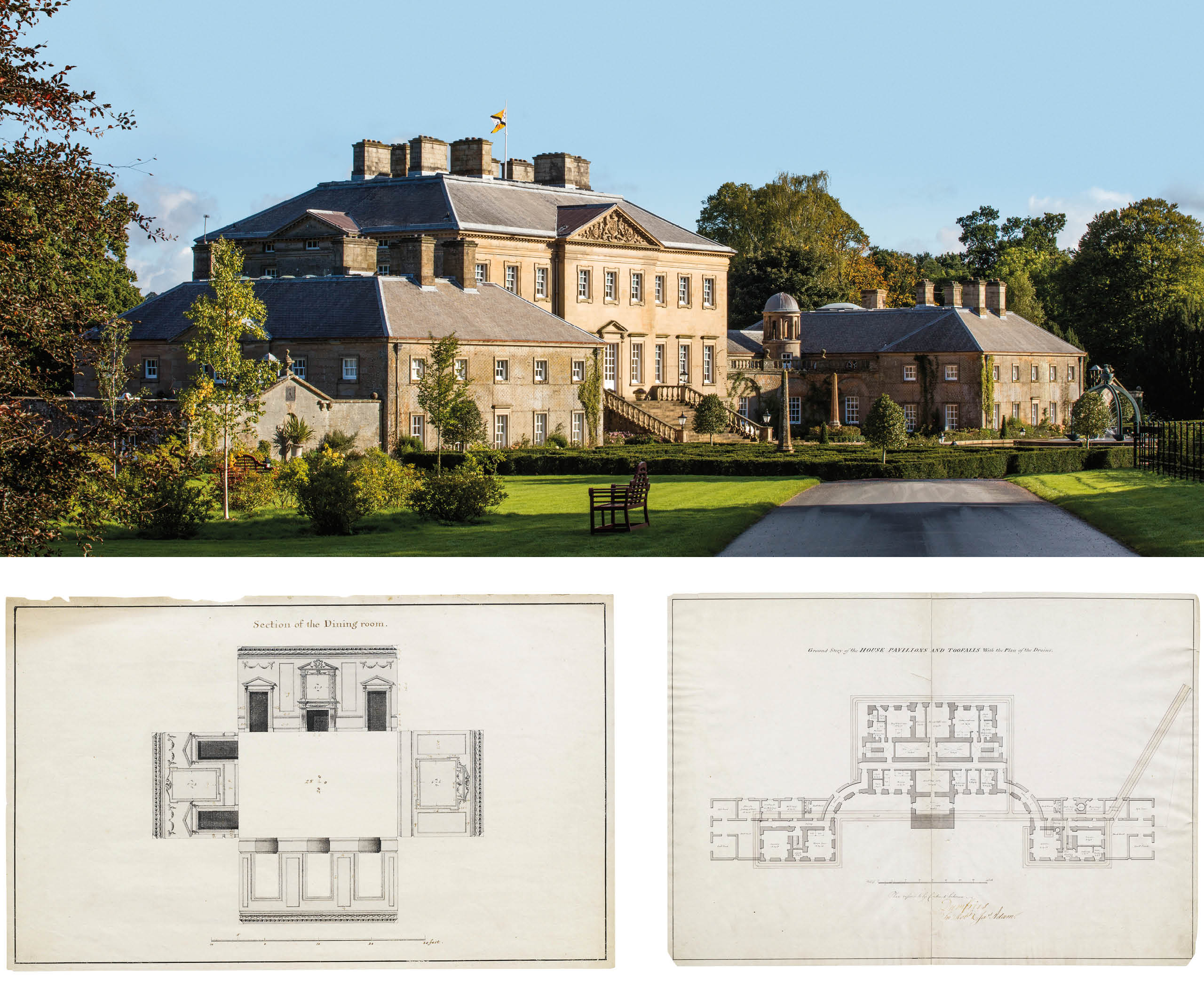

But the Adam who fraternised with the 5th Earl was a young neophyte brimming with ambition. “Dumfries House was his first major commission,” says MacDonald. “Prior to that, he was apprenticed to his father William Adam. The family business had a commission for the Board of Ordnance: things such as army forts and lighthouses.” Robert and his brothers, John and James, all submitted proposal drawings for Dumfries House, but as MacDonald points out, “The drawings on which the house ended up were signed by Robert Adam alone, so it looks as though he had the leading role as designer.”

Barely had the foundation stone been laid, in 1754, than Adam went off on his grand tour of Europe with his friend Charles Hope, leaving John to superintend the build. “Robert ends up seeing the Doge’s Palace in Venice, all the antiquity in Rome and surveys Diocletian’s Palace in modern-day Split, and comes back filled with lots of ideas inspired by classical architecture. He then develops what’s become known as The Adam Style. He became something of a rebel against the Palladian adherents, who insisted on following strict Roman lines and proportion. They copied, while Adam innovated and experimented: the result was a body of work that approached genius.”

The Adelphi – which sadly was demolished in the 1930s – may have been the brothers’ masterwork, but financially it proved to be a disaster. Following the spectacular banking crash known as the Panic of 1772, the difficulty in finding buyers for houses aimed at the city’s Georgian era bourgeoisie led to the Adams disposing of them by lottery (strangely – or perhaps not so strangely – the brothers held a winning ticket). Robert Adam’s legacy is not blighted by the Adelphi affair, and he remains a major influence on both European and American architecture today. Dumfries House was unique in exemplifying his work before the Grand Tour altered his creative direction.

“Adam’s ideas would have been far more informed by experience of real ancient Roman buildings after that,” says Charlotte Rostek. “He went to Europe to find something new and he derived this from what he saw – architectural tombs, ruined bath houses and fortress-palaces which very much influenced what he subsequently did, from tea pavilions to country houses that looked like castles.”

Rostek believes the 5th Earl would have been glad of harnessing Adam’s creative yen before his series of southern European epiphanies: “I think he got exactly what he wished for in Dumfries House as it was built; a very elegant house that came in on budget and represented the culmination of an existing idiom. It was as much an emanation of genius, in its own way, as the novelty that followed.”

Robert Adam Timeline

1728

Born in Kirkcaldy in the Kingdom of Fife to a stonemason father, William, who would go on to become Scotland’s foremost architect of the time.

1743

Enrols at Town’s College (now University of Edinburgh), but abandons his studies the following year and enters his father’s office as an apprentice and assistant.

1748

On the death of his father, along with older brother John, takes on the family business, including work for the Board of Ordnance.

1754

With Dumfries House just under way, embarks on his grand tour, spending nearly five years on the continent studying drafting and drawing skills under Charles-Louis Clérisseau and Giovanni Battista Piranesi.

1761

Becomes Architect of the King’s Works, a role overseeing the building of royal castles and residences.

1792

Dies at the age of 64. Customers including Henry Scott, 3rd Duke of Buccleuch; George Coventry, 6th Earl of Coventry and James Maitland, 8th Earl of Lauderdale are among his pall bearers.

Words: Nick Scott

Photography: Christies Images 2007